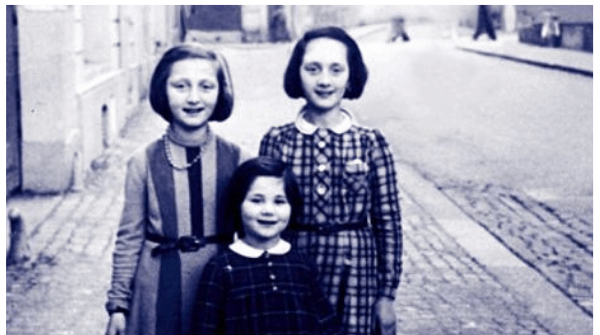

Sylvia Ruth Gutmann was seven years old when, in 1946, she boarded a ship to America with her two sisters. Four years earlier, in a French internment camp, they had been torn away from their parents. While they were hidden for a time in France and then smuggled into Switzerland, their parents were each sent by cattle car to the death camp at Auschwitz and gassed upon their arrival. (pictured above: Sylvia (center), with her two sisters, Switzerland, 1945)

The voyage to America was difficult. The ship was filled with desperate refugees and reeked from the rotting vegetables that were their sustenance. Like many passengers, Sylvia became sick, soiling her dress multiple times. When she and her sisters arrived in New York, they were met by their aunt and uncle, who took in the traumatized girls and helped them start a new life.

Newly enrolled in school and struggling to learn a new language, Sylvia chose a special item for “show and tell”; one that that would help her share her story. She brought in the dress she wore on the ship. She told her classmates about her journey on the smelly ship, and about the murder of her parents. Her teacher, Mrs. Lynch, immediately grabbed Sylvia’s arm, hissing, “You little liar! Be quiet and sit down!” Many years would pass before Sylvia would share her experience again.

That cruel incident took place at a time before the world had fully faced and come to understand the horrors of the Holocaust, as we would in the decades to follow. And yet, seventy years later – we find ourselves with new challenges of knowledge and memory.

A 2018 survey of United States residents showed that forty-one percent of millennials believe that only two million Jews or fewer were killed in the Holocaust. Sixty-six percent of them could not identify what Auschwitz was. In Europe, a third of those polled knew “just a little or nothing at all” about the Holocaust. These numbers are obviously deeply concerning, especially as the very youngest of the survivors who can give first hand witness to the Holocaust are advancing into their eighties.

Through programming connected to the New England Holocaust Memorial, JCRC’s Holocaust education work is centered around survivor testimony. We are committed to providing opportunities for survivors to transmit their experiences for as long as they are able. The Memorial was intentionally placed in the heart of the Boston, along the Freedom Trail and across from City Hall, so that this memory would carry beyond the Jewish community and to all people visiting our city.

In this spirit, to mark International Holocaust Remembrance Day this past Sunday, we invited Sylvia to share her story (documented in her extraordinary memoir) of unimaginable loss and remarkable resilience with an audience of some fifty people at the Brookline Booksmith. And on Monday, we brought survivor Jack Trompetter to Lynn Classical High School. This was the first and perhaps only time that the 400 students assembled will hear a firsthand account from a Holocaust survivor.

JCRC also worked with our partners these past weeks to promote Holocaust remembrance with a Boston City Council commemoration and as part of the “We Remember” social media campaign organized by the World Jewish Congress. Elected officials from across the Commonwealth took part to lend their voices to the chorus of remembrance.

The Boston City Council for International Holocaust Remembrance Day

But faced with the alarming figures about the lack of knowledge, we need to double down to ensure that the Shoah is remembered, through meaningful education of the next generation.

To protect the transmission of history, Holocaust education cannot be relegated to special occasions like the ones this week, but must be fully embedded into the curriculum of all our schools. That is why JCRC has joined with the ADL and others to support legislation mandating Holocaust and genocide education in Social Studies classes across Massachusetts. The bill, filed by Senator Michael Rodrigues and Representative Jeff Roy would ensure a curriculum designed to lift up the very stories and experiences shared by Sylvia, Jack, and the survivor community.

As a community, we understand our sacred obligation to honor the memory of the 6 million Jews murdered by the Nazis. We remember the warning signs ignored and the indifference of those who knew what was being done at that time; an indifference that provided the necessary cover for this horror. We hear and tell the stories of our survivors – so that we may bear witness to their experiences and carry their memories forward. Our work of memory is entwined with our hope for the future; it informs and inspires our efforts to build a future where anti-Semitism, all bigotries, and the indifference that enables them, will someday find no quarter.

Shabbat Shalom,

Jeremy